how to stay safe

Find a local NHS urgent mental health helpline in England

NHS urgent mental health helplines are for people of all ages in England.

You can call for:

- 24-hour advice and support for you, your child, your parent or someone you care for

- help speaking to a mental health professional

- an assessment to find the right care for you

https://www.nhs.uk/service-search/mental-health/find-an-urgent-mental-health-helpline

It's late, but we're waiting for your call

Whatever you're going through, a Samaritan will face it with you. We're here 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Samaritans | Every life lost to suicide is a tragedy | Here to listen

Mental illnesses and mental health problems

https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/mental-illnesses-and-mental-health-problems

Support Directory - Every Life Matters - Suicide Safer Cumbria (every-life-matters.org.uk)

What to do in a suicide emergency

Sometimes thoughts of suicide may become very intense and overwhelming, and a person may struggle to keep themselves safe. They may have made clear plans – they know where, when and how they will kill themselves.

If someone tells you they’re feeling overwhelmed by thoughts of suicide make sure they’re not left alone. Just begin asking about thoughts of suicide generally, if you are worried about the person’s immediate safety ask directly.

If the person feels unable to keep themselves safe and are at immediate risk of attempting suicide stay with them and do one of the following;

- Call 999 – The call is free. Explain what is happening. In this situation, calling an ambulance is the right action to take – not a waste of emergency services time as some people fear. You may also wish to contact emergency services;

- If said person is unable to keep themselves safe

- if the individual has attempted suicide, and either needs medical attention or police intervention

- If someone you are worried does not want to get help or has has gone missing

- Take them to a Hospital A&E– Find your nearest here.

- Contact the NHS Universal Crisis Lines – North Cumbria NHS Universal Mental Health Crisis Line 0800 652 2865 or South Cumbria NHS Urgent Mental Health Support Line 0800 953 0110

It may also be helpful to remove things that someone could use to harm themselves, particularly if they have mentioned specific things they might use. It’s also important to help the person avoid alcohol and drugs when they are at risk.

While these may feel like a drastic steps to take it is a justifiable response to someone’s life being at risk. The police have the resources to find those who are vulnerable to suicide and get help to them quickly, including other emergency services if needed.

Get urgent help If you or someone you know needs urgent support for their mental health you can find the most appropriate numbers to call here. In an emergency For urgent medical attention please call 999 or go to your nearest accident and emergency (A&E) department. If you live in England: NHS Telephone 111 (open 24 hours) Samaritans logo Samaritans Telephone 116123 (open 24 hours) Papyrus HOPELINE Telephone 0800 068 4141 (open 24 hours) If you live in Wales: NHS Direct Telephone 0845 46 47 (open 24 hours) Samaritans logo Samaritans Wales Telephone 116 123 (open 24 hours) Telephone 0808 164 0123 (Cymraeg + open 24 hours) Telephone Papyrus HOPELINE Telephone 0800 068 4141 (open 24 hours) If you live in Scotland: NHS 24 Telephone 111 (open 24 hours) Samaritans logo Samaritans Telephone 116 123 (open 24 hours) Breathing Space Telephone 0800 83 85 87 (open 24 hours) Papyrus HOPELINE Telephone 0800 068 4141 (open 24 hours) If you live in Northern Ireland: Lifeline Tele

Crisis/ Emergency Care options include:

Call Priory hospital if urgent private admission required (020 8876 8261).

Go to your nearest Accident and Emergency (A&E) department for a review by your local

Psychiatric Liaison Service.

Visit www.nhs.uk. Telephone NHS Direct: 111 - 24hr Nurse Advice and Health Information

Service. Most areas have local mental health crisis lines where urgent help, possibly at

home, can also be arranged e.g. in South West London the mental health support line

(outside office hours) is 0800 028 8000.

Make an earlier appointment with your specialist or your GP.

Call Samaritans (116 123) operates a 24-hour service.

Call Saneline: 0845 767 800 (6pm to 11pm)

Call Re-think: 0845 456 0455 (Mon-Fri 10am 2pm)

Call Maytree: (020 7263 7070) offers support and respite to people who are feeling

suicidal: www.maytree.org.uk

Mental health crisis services - Mind

What's a mental health crisis?

A mental health crisis is when you feel at breaking point, and you need urgent help. You might be:

- feeling extremely anxious and having panic attacks or flashbacks

- feeling suicidal, or self-harming

- having an episode of hypomania or mania, (feeling very high) or psychosis (maybe hearing voices, or feeling very paranoid).

You might be dealing with bereavement, addiction, abuse, money problems, relationship breakdown, workplace stress, exam stress, or housing problems. You might be managing a mental health diagnosis. Or you might not know why you're feeling this way now.

Planning for a mental health crisis Nobody plans to be in crisis. You might not like the idea of planning for something you hope won't happen. But it could help to think about what you could do if you start to feel in crisis in the future, and what kind of support might help. Learn about crisis planning What crisis services are there? Exploring different types of support might be something you feel able to do at less difficult times. There’s no wrong order to try things in – different things work for different people at different times. But some types of support might be more suitable for you, or more easily available.

Emergency options

https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/guides-to-support-and-services/crisis-services/accident-emergency-a-e/ What is Accident & Emergency (A&E)? Accident & Emergency (A&E) departments deal with serious and life-threatening medical emergencies, which includes helping people experiencing a mental health crisis. This page covers: When should I go to A&E? How could it help me? How can I access it? When should I go to A&E? If you feel unable to keep yourself safe and you need immediate help – especially if you think you are at risk of acting on suicidal feelings, or you have seriously harmed yourself and need medical attention. How could it help me? Some A&E departments have a liaison psychiatry team (specialist help for mental health) that you can ask to see. If there isn't a liaison psychiatry team, A&E staff might contact other local services such as a crisis team (CRHT) to help assess you. The liaison psychiatry team or mental health team

How can I plan for a possible crisis?

You might not like the idea of planning for something you hope won't happen. But it could help to think about what you could do if you start to feel in crisis in the future, and what kind of support you think you might want.

This page has some suggestions for you to consider. Some people find these ideas useful, but remember that different things work for different people at different times.

You could:

Explore ideas for help and support

It could help to explore possible options for support when things are less difficult, so you have information ready for times when you might need it. For example, you could:

- Talk to your GP – you could ask your GP about options for treatment and support. (For more about talking to your doctor, see our guide to seeking help for a mental health problem.)

- Find your local Mind, and see if they offer support such as day services to help during a crisis.

- Find details of helplines and listening services, including how to contact them and when they're open. It could help to write these details down.

- Read our information on types of mental health problems, including ideas for self-care in a crisis and organisations that may be able to help.

- Try peer support. Talking to people with similar experiences could help you find out about different services, or give you helpful tips to try.

- Make a self-care box. Some people find it helpful to fill a box with things you find comforting or distracting. This means you can personalise what is helpful for you, and have this ready in advance, as it can be very difficult to come up with ideas when you're feeling in crisis.

- Find a recovery college. Recovery colleges offer courses about mental health and recovery in a supportive environment. You can find local providers on the Mind Recovery Net website.

What are crisis teams? Crisis teams can support you if you have a mental health crisis outside hospital. You may also hear them referred to as crisis resolution and home treatment teams (shortened to CRHT or CRHTT). Or you might find that your local service is called something different. This page covers: How could a crisis team help me? How can I access a crisis team? I had a crisis at the GP surgery [...] so I saw the crisis team right quick (within four hours!). Needless to say in these circumstances the crisis service was comparatively brilliant. How can a crisis team help me? Crisis teams can help if you need urgent mental health support. This includes times when you might otherwise need to go to hospital for your mental health. For example, this may be because of psychosis, severe self-harm or suicide attempts. The team usually includes a number of mental health professionals, such as a psychiatrist, mental health nurses, social workers and support workers. Crisis teams can:

Emergency GP appointments in England

To access this service in England, you can:

- contact your local GP surgery. You can find GP surgeries on the NHS website. If the surgery is closed, you should hear a recorded message explaining what to do, or you can call 111 instead.

- call 111, a free 24-hour NHS helpline that can help you access local services including GPs. Find out more about this service, including options for people with hearing difficulties, on the NHS website.

Emergency GP appointments in Wales

To access this service in Wales, you can:

- contact your local GP surgery. You can find GP surgeries on the NHS Direct Wales website. If the surgery is closed, you should hear a recorded message explaining what to do, or you can use the options below instead

- contact your local out-of-hours service. To find their details, see the Health in Wales website

- call 111, a free 24-hour NHS helpline. In Wales, you can call 111 and select option 2 to access urgent mental health support. Find out more about this service on the NHS 111 Wales website

What are crisis houses? Crisis houses offer intensive, short-term support to help you manage a mental health crisis in a residential setting, rather than in a hospital. This page covers: When should I use a crisis house? How could it help me? How can I access it? When should I use a crisis house? As an alternative to going into hospital, for example if you don't feel safe at home overnight, or things at home are contributing to you being in crisis. How could it help me? Crisis houses can vary and offer slightly different services. However, they usually offer: overnight accommodation a small number of beds a home-like environment intensive treatment. Crisis house, sanctuary or safe haven? Services with these names can be very similar. The main difference is that crisis houses usually offer overnight accommodation with a bed for you to sleep in. Services described as sanctuaries or safe havens usually don't provide somewhere to sleep or live in. But they might be open overnight as a

What are emergency GP appointments?

Your local GP surgery should be able to offer you an appointment to see a doctor quickly if you need urgent support for your mental health. This is often called an emergency appointment or same-day appointment.

This page covers:

When should I make an emergency GP appointment?

If you need urgent support for your mental health, but you feel able to keep yourself safe for a short while until your appointment.

How could it help me?

An emergency appointment involves seeing a doctor quickly – usually the first appointment with an available doctor. If it's not with your regular GP and you'd like to see them too, you can ask your surgery about booking a follow-up appointment.

What might happen at the appointment?

In your appointment, the doctor might:

- ask about what's happening for you currently, including your moods, thoughts, behaviours and any recent events that have contributed to you feeling in crisis

- provide information and advice, for example, about other local services you can contact yourself

- prescribe or adjust medication, which might be to help you cope with symptoms you're experiencing or to try to reduce side effects that are contributing to how you're feeling

- refer you for more support, for example to a crisis team (CRHT) or potentially for hospital admission.

(For more information on talking to a GP, what might happen at the appointment and whether it's confidential, see our guide to seeking help for a mental health problem.)

become more aware of your triggers

Dr Persaud will discuss your specific personal safety plan

Understanding Mental Illness Triggers | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness

Understanding Mental Illness Triggers

By Katherine Ponte, JD, MBA, CPRP

A trigger, sometimes referred to as a stressor, is an action or situation that can lead to an adverse emotional reaction. In the context of mental illness, referring to triggers usually means something that has brought on or worsened symptoms.

In the ongoing dialogue about mental health, we don’t talk enough about triggers. Most often, the discussion focuses on what happens after a person has been triggered, which is when the situation is much harder to address. Understanding, identifying and working to prevent triggers can be more empowering and effective.

Understanding Triggers

Triggers are individualized experiences that vary widely from person-to-person. For example, a trigger may elicit a physical reaction, such as heavy breathing or sweating. A trigger can also spur an emotional reaction, like thinking “I am being attacked, blamed, controlled, disrespected, hurt and judged.” After experiencing a trigger, a person may feel overwhelmed, powerless, scared, unloved and weak, among many other feelings. These feelings can be very difficult to address and quite detrimental to mental health.

A person’s behaviors based on their emotional reaction can range from relatively minimal to serious, such as acts of violence. Someone exposed to a trigger while symptomatic may be more vulnerable and the emotional reaction may be stronger. Additionally, a trigger can impair judgment and some people may lack insight about their reactions.

It is important not to assume that you understand the emotional response of someone who has been triggered or suggest that someone who has been triggered is overreacting, being “too sensitive” or being irrational, even if the trigger may seem insignificant.

Types Of Triggers

Many different stimuli can be possible triggers, and they are often strongly influenced by past experiences. Personally, as someone who lives with mental illness, I have experienced numerous triggers when I’ve been symptomatic. These triggers have led to extreme discomfort, family conflict, onset of illness, worsening of symptoms, episodes and hospitalizations.

External triggers: In the summer of 2006, I became engrossed watching the inexplicable war and tragic loss of life in the middle east on CNN. This triggered a severe psychotic manic episode. Similar geopolitical events triggered me twice more. Each time I was hospitalized. To prevent this trigger from repeating, I stopped watching televised news.

Internal triggers: I was triggered by feelings of abandonment when my spouse avoided contact with me to minimize conflicts. I would at times spontaneously angrily erupt. To address these feelings, I talked to my spouse and let him know how our strained communications made me feel, and he reassured me that he had no plans to leave me.

Trauma triggers: I live near the hospital where I experienced a traumatic hospitalization. It was along a convenient route for me to access public transportation, but every time I walked by it, I recalled that hospitalization and was “re-traumatized.” After being triggered several times, I decided no longer to walk past the hospital and took a longer, alternative route.

Symptom triggers: A lack of or reduced need for sleep has occasionally triggered the symptoms of my bipolar disorder. In this situation, I quickly address any sleep disruption, often with a medication adjustment in consultation with my doctor.

Ways To Cope

There are many possible coping strategies. Strategies should seek to eliminate, avoid and reduce the impact of triggers and emotional reactions. Each person must identify what works best for them through trial and error. Different coping strategies may work for different triggers and emotions.

Learn to identify: Consider reactions to past triggers; who or what was involved, where, when and why it took place. Observe patterns and obvious signs of risk to prevent a similar situation (like ceasing to watch televised news).

Make a plan to address: Create a plan to address triggers and emotional reactions. You may want to talk to loved ones or your treatment team to let them know how they can best help you when you are triggered. Be sure to carefully address triggers that occur repeatedly, because each time they do, the emotional reaction may be greater.

Try problem-focused coping: Confront your stressor directly or try to find a solution to the stressor. For example, driving your kids to school may cause you to worry, because you’re afraid you might arrive late to work. Instead, you can ask someone else to drive your kids to school.

Try emotion-focused coping: When you cannot eliminate or avoid a trigger, focus on regulating your reaction to a stressor which may help reduce the stressor’s impact. For example, meditation can help reduce stress, anxiety and depression.

Communicate if someone is triggering you: A person triggering another person often does so unintentionally. Talk to them about their actions and their impact to clear up any misunderstandings and consider possible solutions. Have an open, calm and understanding dialog. Be willing to work with them. If the person who is triggering you refuses to act sensitively, it may be best to set clear boundaries.

Find the right therapy: Specific types of therapy have been shown effective in addressing triggers. Specific therapies especially helpful for addressing trauma triggers include exposure therapy and EMDR therapy.

Reality-check your thoughts: To minimize the escalation of thoughts and feelings, it may be helpful to “reality check” thoughts to assess their reasonableness. A few ways to do this include:

- Fact checking: Consider the facts and whether they support your interpretation.

- Apply cognitive distortions: Identify faulty or inaccurate think, perceptions or beliefs.

- Reframe: Reshape automatic negative thoughts into positive thoughts.

- Proportionality: Ask yourself, is the reaction disproportionate to the trigger?

Look for trigger warnings: Triggers warnings can help alert you to triggering material, especially materials related to suicide or violence. Sometimes, an article will provide a trigger warning at the start of the piece. You can even ask others to provide you with a trigger warning about materials they share.

Practice self-care: Prioritizing your mental health can help build resilience against potential triggers. You can start by talking to someone, such as a loved one, friend or therapist. You may also want to practice mindfulness, meditation, deep breathing or journaling.

It’s difficult to control our triggers; however, we can learn from our experiences. We can apply what we learn to manage and limit the risk of being re-triggered. We can’t diminish or dismiss the trigger or only focus on what happens after we’re triggered — we must also focus on what we can do beforehand.

Each time we’re triggered is a learning opportunity that can help us manage our reactions in the future. If we can’t control the trigger fully, we may be able to limit the emotional reaction to it before it becomes problematic and harder to address. We might even be able to prevent the trigger by preparing for it. We can have some control, and anything that gives us a little control over our mental illness can help keep us well.

Katherine Ponte is happily living in recovery from severe bipolar I disorder. She’s the Founder of ForLikeMinds’ mental illness peer support community, BipolarThriving: Recovery Coaching and Psych Ward Greeting Cards. Katherine is also a faculty member of the Yale University Program for Recovery and Community Health and has authored ForLikeMinds: Mental Illness Recovery Insights.

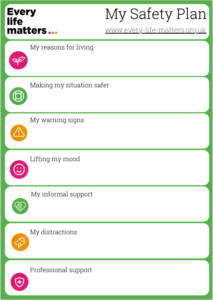

Safety Planning - Every Life Matters (every-life-matters.org.uk)

Many people will have thoughts of suicide - but thinking about suicide does not make it inevitable that you are going to take your own life. A safety plan helps prevent us turning these thoughts into actions.

A Safety Plan focusses on keeping you safe right now

A Safety Plan includes what you would do, and who might support you, in a crisis. They might include distraction techniques to help you get through the next seconds or minutes as thoughts of suicide becoming overwhelming, how you can make your immediate environment or situation safer, who you can contact when things get really tough, and what you can do in an emergency.

Safety Plans take a stepped approach. They can help us manage those fleeting thoughts of suicide that emerge at the edge of your mind – through to situations where the desire to die becomes so overwhelming we no longer think we can keep yourself safe.

![]()

Make your Safety Plan before you reach crisis point. Being prepared is key. Start writing it now. Its also OK if you feel you can’t complete all of it right now, fill in what you can and come back to the other sections later.

Ask someone to help you write your plan. Find someone else who can support you through it, and bounce ideas off – like a family member, friend or mental health worker. If you name someone in your plan, tell them, and if you can share your safety plan with them.

A safety plan needs to belong to you. It is a very individual plan. Someone can help you develop it but ultimately you need to decide what goes into it, and what works for you.

A safety plan is a practical tool to help you keep safe. It focuses on managing thoughts of suicide and it is not a wellbeing plan or a long term plan to deal with low mood. But do think about what support you might need to make changes in the long run to protect you from thoughts of suicide.

It needs to be a plan that is going to work for you. Make sure you have access to your plan when you need. Have a copy on your phone and if you can, share it with relevant family, friends and professionals such as your GP or mental health worker. Review your plan every so often to check its still relevant.

Write your Plan

You can download a copy of our Safety Plan template here as a PDF.

You don’t have to use these and may prefer to find a more personalised way of constructing your own.

Part 1

Reasons for Living

It is important to remember that as well as having reasons for dying there are also reasons for living. Have these in your plan as a reminder of your reasons to stay alive – they be written down, or photos, or objects. They may be people or animals, commitments or future plans or the hope that things may change.

They may also be thoughts or beliefs relating to

Yourself: Such as – I care enough about myself to live – I have the courage to face life – No matter how bad I’m feeling I know it will not last – I’m afraid of the unknown – I’m afraid of actually killing myself

Family and Friends: Such as – I don’t want my family to feel guilty or to suffer – I have a responsibility or commitment to my family or friends – I love them and if I left them they may question whether I did love them

Beliefs and Hopes: Such as – I believe that I can find a purpose in life – I’m curious what may happening the future – Life is all we have – its better than nothing – Although life feels really tough, things may improve.

Some people make hopeboxes either virtual ones or actual ones with reminders of people and places that are important etc as well as things to sooth and distract

Part 2

Making your situation safer

Do you have a plan of how you would take your own life? Do you know what you would use?

Consider making it harder for yourself to get hold of them, especially when you are feeling in crisis. Can you remove these means from your house? Or give them to a friend or family member to keep.

If you have prescription medication can you can ask that you receive your prescription in smaller amounts? Or ask a friend or family member to hold on to them and allow you a weeks supply at a time?

If you don’t have a plan it is still important to look at how to keep yourself safe.

![]()

- Be aware that alcohol and drugs may make you act more impulsively, or limit your self-control, so it is important to limit consumption.

- Some people and some places may lower our mood when we are feeling vulnerable, or trigger thoughts of suicide. Be aware of them and avoid them if you can.

- If you have previously attempted to take your own life before think about what made it harder to stay safe then. Learn from the experience.

Part 3

Recognising the warning signs

How do you know you’re not feeling safe?

- What thoughts and feelings happen before you start to have thoughts of suicide? Especially around hopelessness or feeling trapped?

- Are your thoughts of suicide increasing in intensity or frequency?

- Are there changes in your behaviour? Perhaps drinking more, isolating yourself, increased self-harm, recklessness or other negative coping habits?

- Could other people close to you recognise these signs and help you become aware of them?

Do you know what may trigger these feelings?

- This may be certain events or times of year, such as an anniversary, or during winter.

- It might be about what’s happening in your relationships or a life event that has left you feeling out of control or feeling helpless.

Part 4

Identify what may lift mood

The first stage of managing those emerging thoughts of suicide is knowing how to lift our mood and distract ourselves. This might include:

- Physical – go out for a run or a walk, head to the gym

- Creative – draw, colour, make a playlist, bake

- Productive – make lists, have a clear out, garden, write yourself a letter

- Chilling out – meditation, have a bath, listen to music, spend time with a pet, game, watch your favourite movie (on repeat if necessary)

- People and places – can you go out and catch up with a friend, play football with mates, go to a museum, go to a faith centre.

Think about what works for you, be realistic, and remember different things might help at different times.

![]()

We probably know some people who are great at distracting us but we wouldn’t necessarily want to speak to them about how we are feeling – get them on this part of your plan. Also be aware of people or places who don’t help our mood, or we need to avoid.

Ideally we want to have a few different options at this point for different times/circumstances. We don’t want to have our only option as running if you are a fair weather runner and we live in Cumbria!

If this is the first time you are feeling like this and you are not sure what may work – don’t worry – look at some of the options above and think would any of these work for me, what do you feel might and give it a go.

Remember its not a ‘one size fits all’ what works for one person may not work for another – but sometimes it maybe worth giving things a go.

Part 5

Identify your informal support

If your chosen distractions are struggling to lift your mood, and thoughts of suicide are still present, or growing, reach out to informal support.

These are the safe and trusted people, or organisations, that you feel comfortable to talk about how you are feeling – including talking about your thoughts of suicide.

Get at least three of these on your Safety Plan. They could include;

- Friends, family or colleagues.

- A key worker or volunteer at an organisation that supports you.

- A local or national telephone or text Helpline such as the Samaritans or CALM

- An online support forum

- Have a look at our Getting Help page for more information about where to get support

![]()

Have at least three named people/helplines on your plan. Make sure to include contact details on your plan and put their numbers in your phone for when you really need them.

If you put friends, family or colleagues in your plan tell them. And if you feel comfortable share your Safety Plan with them. You can also share other information with them from this website about supporting someone with thoughts of suicide.

Think about having a “cue” word or action between you. Sometimes it can feel really hard to start the conversation. Having a “cue” word or action can mean that the person named on your plan can help you start the conversation.

If you are not able to identify any friends or family to include at this stage – that is ok. There is lots of help out there. Have a look at our Getting Help pages. There are lots of helplines listed there with trained staff who are there to listen confidentially to whatever you need to talk about, and in your own time.

Part 6

Distractions

If the thoughts of suicide are getting stronger – and we are not able to lift our mood or talk to anyone, or talking hasn’t helped – we need to take further proactive steps to keep ourselves safe.

You may be overwhelmed – but it is so important to remember these feelings will pass.

Studies suggest that thoughts of suicide are strongest for 15-30 minutes. You need to focus on how you will get through this period of time.

Step by step. Minute by minute. Stay safe for now and not act on the urges. .

This is where your Safety Plan is so important. You need distractions and activities to get you through one minute at a time. People have used some or all of the following – find what works for you.

- It could be some of the distractions listed in Part 4

- Breathing exercises

- Games on your phone

- Distracting self so the urge passes.

- Positive statements that you use to inspire you or a faith

- Your Reasons for Living or Hopebox

Have a look at Papyrus’s Coping Strategies and Distraction Techniques for more ideas.

Part 7

Getting professional support

If you are in crisis or no longer feel able to manage the thoughts of suicide then identify in your Safety Plan how you will get professional help.

- Are you connected with any mental health professionals? Do you have a Care Co-ordinator for example? If you are, do you know how to get hold of them in a crisis? Get their contact details in your plan and in your phone.

If its your first time in crisis

- Call the 24hr Universal Mental Health Crisis Lines – North Cumbria 0800 652 2865 – South Cumbria 0800 953 0110

- Contact your GP for an emergency appointment.

- Call NHS 111, they can direct you on how best to get help or how to access out of hours’ doctors.

Again get these contact details in your plan.

Remember when you go to see your GP its OK to take a family member or friend with you for support. Be open about your thoughts and feelings, including suicide, and bring a copy of your Safety Plan with you.

![]()

Are you in immediate danger of taking your own life? Have you already harmed yourself or taken an overdose? Do you have imminent plans for killing yourself? Are your thoughts of suicide particularly intense right now and do you feel unable to stay safe?

If so, seek immediate help now

- Call 999 – The call is free. Explain what is happening to you. You can stay on the line while you wait for help to arrive.

- Or go to a Hospital A&E – Find your nearest here.

- If you have someone else around ask them to call 999 for you and stay with you wait for the ambulance, or take you to A&E immediately.

Getting Help

If you are really struggling to cope, or feel overwhelmed by difficult feelings or thoughts of suicide, then reach out for professional help. It’s OK to ask for more support to see you through this difficult time.

Find out more about Getting Help to support your mental health and wellbeing.

Feature something

Support Directory - Every Life Matters - Suicide Safer Cumbria (every-life-matters.org.uk)

Support Directory

Browse our directory for more information about the Support and Services available to you across Cumbria, Nationally and Online.

Suicide & Mental Health Crisis – What to do in an emergency

Suicide and Crisis Support

Mental Health – Telephone and Text Helplines

Mental Health – Online Support Communities

Mental Health – Self-help Guides

Mental Health – Recommended Apps

Mental Health – Support in Cumbria

Mental Health – NHS Support in Cumbria

Mental Health – National Support

Self-harm Support

Children and Young People – Support in Cumbria

Children and Young People – National Support

Debt, Benefits, Housing, Employment – Support in Cumbria

Debt, Benefits, Housing, Employment – National Support

Domestic Abuse, Sexual Assault and Victim Support

Drug, Alcohol and Gambling Support

Bereavement Support

Suicide Bereavement Support

Veterans Support

Women’s Support

Mens Support

Health, Disabilities and Learning Disabilities

Carers Support

Older Adults Support

Farming Communities Support

LGBTQ+ Support

BAME and Equality

Copyright © 2024 Dr Raj Persaud FRCPsych Consultant Psychiatrist 10 Harley Street - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy